I’ve been reading Rob Hopkin’s new book How to Fall in Love with the Future. Building on his previous work on imagination, he makes a compelling case that if we can’t imagine a future where everything turns out okay, then we are very unlikely to create that future.

Meanwhile, dystopian visions of climate and biodiversity collapse, the rise of authoritarianism and AI takeover are all too pervasive.

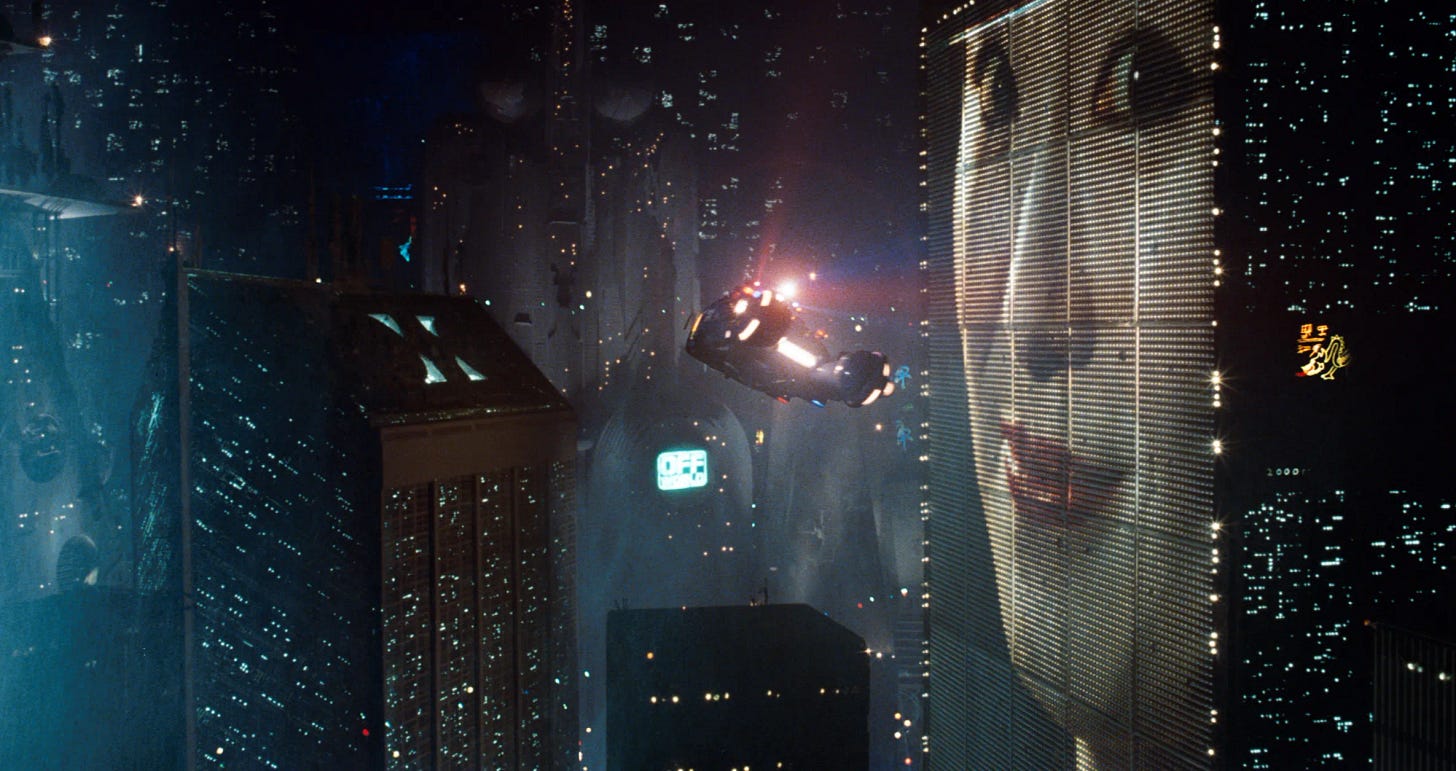

Looking out at the cold, impersonal skylines of many major cities, it can feel like we’re not far from the dystopia of Blade Runner or other sci-fi worlds. As it turns out, this is no coincidence.

While exploring this topic, I stumbled on an article on Inverse titled How Science Fiction Dystopias Became Blueprints for City Planners. According to researcher Steve Graham, science fiction has influenced contemporary architecture and urbanism - particularly our obsession with skyscrapers and vertical cities.

Before I move on, I want to make clear: I’m not suggesting that science fiction is the sole reason why the world seems increasingly dystopian. We can also blame capitalism, colonialism and extractive technologies to name a few. But the urban forms that signify progress into the future are clearly and heavily influenced by works of science fiction and futuring.

Let’s look at some examples.

The assumption that ‘the future’ meant ever larger and vertically spreading cities goes back to the earliest science fiction. The 1899 novel The Sleeper Awakes by H.G. Wells is set at the turn of the 22nd century. In this future, Britain has fully urbanised into four gigantic megastructure cities. London is encased in a glass dome, separating it from nature. It’s not hard to see how such notions inspired Modernist architects like Le Corbusier.

For the current generation of architects and urbanists, 1982’s Blade Runner seems to be a key cultural reference. As journalist Peter Suderman puts it, ‘Blade Runner…helped set our expectations for what cities should look like.’And I don’t just mean as an unconscious reference point. According to Graham, the visual designer from Blade Runner has literally consulted with elites in the Middle East (one assumes the likes of U.A.E and Saudi Arabia) about futurist architecture.

Another interesting example from the article is that the architect of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the world’s tallest building, was directly inspired by the Emerald City in the Wizard of Oz.

This phenomenon isn’t just limited to the Gulf states. London’s grey, corporate office districts are often used as sets for science fiction films. Recent examples include Ready Player One and Star Wars: Rogue One.

In interviews, starchitect Bjarke Ingels often references his love of science fiction as a driving force behind his architectural design. To be fair, BIG’s work generally has more utopian intentions and is more human-centric compared to typical futuristic visions.

Zaha Hadid Architects’ futuristic forms appear to be heavily inspired by technological visions of the future. Worryingly, ZHA Principal Patrik Schumacher has written about how architecture needs to abandon ‘woke’ social and environmental concerns and focus solely on ‘architecture’s unique societal function: the provision and continuous innovation of spatial frames that order and articulate social interactions’. Call me a woke snowflake but this sounds pretty dystopian to me.

Why anyone would want to intentionally create dystopian cities still seems to be a mystery. Perhaps if you’re rich and powerful, the narratives of elite dominance over nature and people in many sci-fi worlds actually appear utopian. As Graham says in the Inverse article:

There’s a really startling and disturbing similarity between a lot of these sci-fi vertical dystopias and the current practice in, say, the Gulf, where the elites inhabit their penthouses and fly around in helicopters and business jets while literally thousands of workers are dying every year to construct these edifices.

Telling new stories about the future

Following a trip to China last summer I wrote a Substack article titled Is Shanghai 20 years in the Future?. The city’s downtown skyscrapers, clean streets, new metro lines and electric vehicles make it feel futuristic.

But I never stopped to think why gleaming skyscrapers and high-technology feels like an inevitable part of the future - as if we are destined to make science-fiction into science-reality.

It’s because of the stories our culture has been telling about the future.

If these stories are intertwined with ecological destruction and social inequality, maybe it’s time to start telling new stories?

‘…there is a unique task which accompanies fighting climate change: imagining what the world looks like in which we do succeed. Without direction, we cannot make demands. Without an image of what a changed world looks like, where does hope lie? If we persist in thinking that positive change is impossible, we will prove ourselves right. If we are to commit ourselves to consequential change, we need a positive vision’. - Isaijah Johnson (Source)

Rob Hopkins likes to take things that already exist, like car-free neighbourhoods, local food networks and creativity-led schools, as examples of what the near future could look like.

In workshops, he invites participants to ‘time travel’ in their imaginations to a version of 2030 where we did all we possibly could have done to address the many crises we face. Not utopia, just a future where ‘things turn out out okay’. Participants’ experiences of future neighbourhoods are often strikingly low-tech and friendly.

‘What fascinates me is how similar the answers are. Every time. “The birdsong is so much louder”. “The air smells like Spring”. “There are many less cars”. “People are much less stressed, and I feel much more part of a community”. “People work less”. The same answers every time. In spite of having done it so many times, no-one ever said “it’s great, we have a new IKEA, four times bigger than the one we had in 2022.”’ - Rob Hopkins (Source).

Others like to push the boat out further. Solarpunk is a speculative fiction and art genre that imagines ‘low carbon, high life’ futures. Futures where humanity addresses the climate and biodiversity crises by deploying sustainable technologies, regenerating nature and creating social equality. It’s a counterpoint to the dystopian Cyberpunk worlds we all know (and some seem to love).

Solarpunk visions depict green cities where communities grow food and power their modest lifestyles with solar panels and wind turbines. The punk aspect is generally anti-establishment and anti-capitalist. To me, what is striking is how realistic and reasonable many Solarpunk vision are. We have the technology and means, we’re not waiting on any new sci-fi technologies to make the world better for everyone.

Another movement is Afrofuturism, which addresses the dominance of western thought and colonialism in most discussions on the future by centring the cultures of Africa and the African diaspora. The Marvel film Black Panther is perhaps the most famous work inspired by Afrofuturism, although there are also many works of music, visual art and literature associated with it. These visions show us how our cities and buildings can be steeped in local traditions while still looking to the future.

These movements illustrate how diverse, local cultures can thrive and coexist rather than assuming a dominant, hegemonic galactic empire or ‘Big Brother’ that most mainstream science fiction suggests.

How to get started

The good news is that you don’t need to be an author, artist or time traveller to create new stories of the future. It starts with closing your eyes and imagining, what if everything turned out okay? If you’re an educator or leader, you can lead people through imagination workshops and build collective visions.

Once you know what a good future looks and feels like, you can start working towards it and challenging the dominant narratives of dystopia.

Personally, I’m going to start bringing these imagination sessions into my teaching work. I often have to explain the ‘doom and gloom’ of climate science before moving onto exploring urban climate mitigation and adaptation. The problem with this is that it creates a framing of ‘let’s try to avoid the worst outcomes’ rather than actively creating good places.

My hope is that by anchoring people is positive visions of the future, the work of addressing the climate and biodiversity crises becomes inspiring and hopeful.