5 Urbanism Lessons from Copenhagen (beyond bikes)

Copenhagen is famous as a cycling city. But beyond this, there is a lot to learn about their approach to creating a liveable city and planning new neighbourhoods. Here’s 5 lessons I learned on a recent trip to the Danish capital.

Please forgive the gloomy weather and my amateur photography. The city really is more beautiful in real life!

1. Adaptation, not preservation. Making a historic city more liveable

Copenhagen is home to impressive heritage buildings. But the Danes don’t seem to be too precious about their preservation. It is common throughout the city for older properties to be retrofitted with external balconies to give residents some outdoor space and enhance their quality of life (and presumably to raise the property price). A lack of outdoor space is a common complaint for those who live in apartments buildings in many major cities. If we can suspend our need to preserve historic cities looking exactly as they are, then this presents a straightforward solution. It’s a perspective that reflects that the fact that cities are always changing and evolving.

Internal courtyards at the centre of street blocks have also drastically changed to meet modern standards and enhance liveability. I stayed with some friends in the city who explained that their internal courtyard would have once been home to outhouses and rubbish piles. Now it’s a green communal garden with a playground, bike storage and discrete bin storage. It even has an attractive rainwater retention pond at the centre, a mini-example of sustainable drainage (see photo above).

2. Start with activation, then regeneration

Several areas in Copenhagen are in transition from industrial use to mixed use neighbourhoods. The former Meat Packing District is home to a complex of functional low-rise industrial buildings. Instead of ripping them down for a new masterplan, they have been adapted for a range of quirky independent uses like pubs, bakeries and specialist grocery stores.

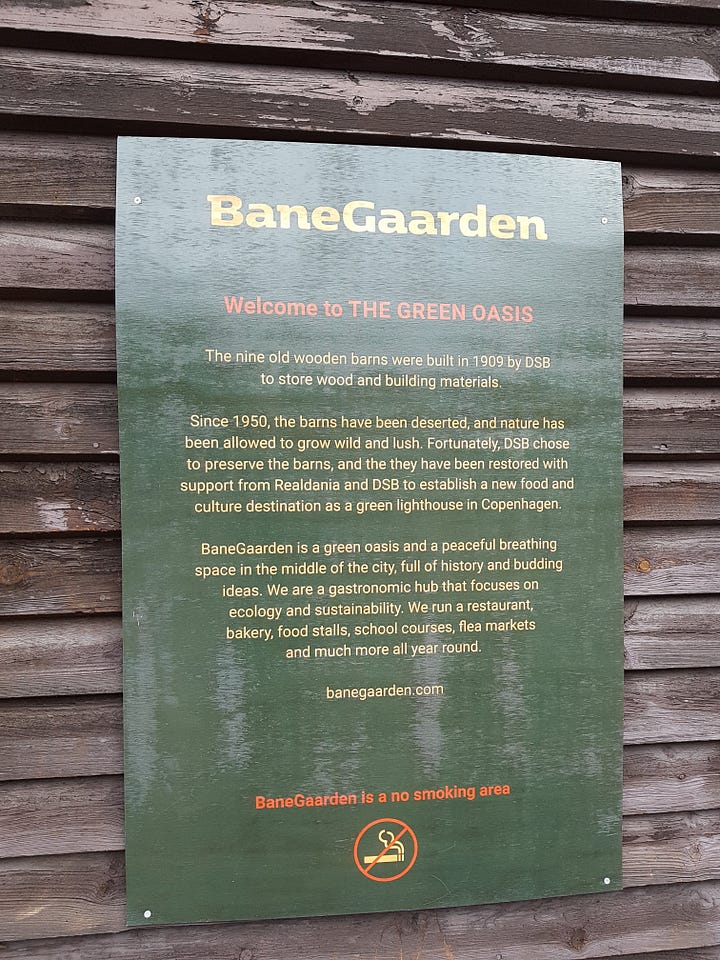

Elsewhere, at BaneGaarden, deserted timber storage barns are finding new life with more independent food and drink offerings. Around it the area is changing with a beautiful student housing scheme and installations for the Festival of Architecture. There is also a small biodiverse park.

Instead of starting with a grand plan and building out brand new apartments, the city is working with what is already there, making space for the community and building a buzz in these neighbourhoods before anyone moves in. Once the first permanent residents do move in, it should already feel like a real neighbourhood, because in many ways it has been for years.

3. Bring water into everyday life

Copenhagen sits on an island and has a long historical relationship with the sea. As major shipping and industry has reduced, the city is making an effort to bring access to safe and clean water into everyday life for citizens. New neighbourhoods like Sluseholmen are built partly on reclaimed land and integrate canals and direct access to the sea. There are lots of opportunities to jump in or drop in a kayak. In fact, apartment buildings here have direct access to the water and a communal selection of shared boats. Some even have direct access to the water from their private terrace. While strolling around (in January no less) I saw a mobile sauna slowly gliding across the bay with some people inside, enjoying the view while steaming.

Apart from bringing joy, easy access to cold water has incredible health benefits. Many people around the world now do ice baths or cold showers as part of their wellbeing routine. Imagine having access to the north sea on your doorstep for a morning plunge?

4. Natural, local materials

Something that struck me in new developments was the use of informal, natural materials like gravel in the landscape design. Of course there are asphalt streets and hard paving. But there are also lots of areas with natural surfaces, which lend a slightly scruffy, unfinished aesthetic. My friend, who works as an architect in the city, explained that as part of a wider push for decarbonisation, designers are specifying natural, low carbon materials wherever possible. It also allows for water infiltration, which helps with flood resilience.

This thinking of course extends to buildings too, with many examples of timber. In the UK, a timber structure is generally not used in residential buildings because of fire safety concerns. It’s interesting to see examples of timber homes and apartment buildings in Copenhagen – perhaps a matter of culture and experience using timber for centuries.

5. Good urbanism needs equality and safety

There are many more interesting aspects of Copenhagen’s urbanism. I was stunned to see bikes everywhere not locked to anything. In London, an unlocked bike would be stolen in no time. But in Copenhagen it’s typical for people to simply lock the back wheel to the frame so it can’t be cycled and leave it resting against the wall. A similar culture shock came when I saw a new school built with no fencing. The playground and outdoor areas were totally open for anyone to use. Again, in the UK, child safety is very serious and there are strict regulations on the need for fencing and locked gates around schools. These examples make me realise that some aspects of ‘good urban design’ can only be achieved in societies where there is low crime and a high level of trust among individuals.

This goes beyond block structure and architectural design, it’s about history, politics and economics and perhaps why exemplary nordic projects are so hard to replicate in many other countries.

Thanks for reading and I hope you found it useful and inspiring. Let me know your thought by commenting on the article.

If you are enjoying the newsletter, share it with a friend or colleague!

Until next time,

Ross